Excerpt of a Letter from Erwin Hirsch to Stefan Jakobowicz, January 31, 1942

- 1942-Jan-31

Rights

Download all 2 images

PDFZIPof full-sized JPGsDownload selected image

Small JPG1200 x 1543px — 431 KBLarge JPG2880 x 3703px — 2.6 MBFull-sized JPG5352 x 6882px — 8.6 MBOriginal fileTIFF — 5352 x 6882px — 105 MBErwin Hirsch, a chemist residing in Saint-Juéry, France, describes the victimization and disenfranchisement of Jewish scientists to his colleague in New York, Stefan Jakobowicz. Hirsch and many of his colleagues have been removed from their employment, forced to do hard labor, or sent to concentration camps. Hirsch inquires if current scientific literature could be procured for them in North America and sent to Europe, so that they can remain informed on developments in biology, chemistry, physics, and medicine.

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Author | |

| Addressee | |

| Place of creation | |

| Format | |

| Genre | |

| Extent |

|

| Language | |

| Subject | |

| Rights | In Copyright - Rights-holder(s) Unlocatable or Unidentifiable |

| Credit line |

|

| Additional credit |

|

| Digitization funder |

|

Institutional location

| Department | |

|---|---|

| Collection | |

| Series arrangement |

|

| Physical container |

|

View collection guide View in library catalog

Related Items

Cite as

Hirsch, Erwin. “Excerpt of a Letter from Erwin Hirsch to Stefan Jakobowicz, January 31, 1942,” January 31, 1942. Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, Box 9, Folder 12. Science History Institute. Philadelphia. https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/jd3onzn.

This citation is automatically generated and may contain errors.

Image 1

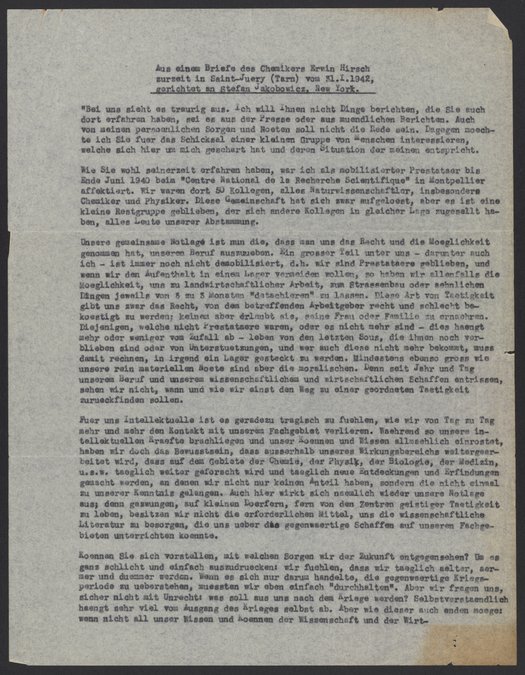

Aus einem Briefe des Chemikers Ervin Hirsch zurzeit in Saint-Juery (Tarn) vom 31.1.1942, gerichtet an Stefan Jakobowicz, New York .

"Bei uns sieht es traurig aus. ich will ihnen nicht Dinge berichten, die Sie such dort erfahren haben , sei es aus der Presse oder aus muendlichen Berichten. Auch von meinen persoonlichen Sorgen und Noeten soll nicht die Rede sein . Dagegen moechte ich Sie fuer das Schicksal einer kleinen Gruppe von Menschen interessiere, welche sich hier um mich geschert hat und deren Situation der meinen entspricht.

Wie Sie wohl seinerzeit erfahren haben, war ich als mobilisierter Prestataer bis Ende Juni 1940 beim "Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique" in Montpellier affektiert. Wir waren dort 50 Kollegen, alles Naturwissenschaftler, insbesondere Chemiker und Physiker. Diese Gemeinschaft hat sich zwar aufgeloest, aber es ist eine kleine Restgruppe geblieben, der sich andere Kollegen in gleicher Lage zugesellt haben, alles Leute unserer Abstammung.

Unsere gemeinsame Notlage ist man die, dass man uns das Recht und die Moeglichkeit genommen hat, unseren Beruf auszuueben. Ein grosser Teil unter uns - darunter auch ich - ist immer noch nicht demobilisiert, d.h. wir sind Prestataere geblieben, und wenn wir den Aufenthalt in einen Lager vermeiden wollen, so haben wir allenfalls die Moeglichkeit, uns zu landwirtschaftlicher Arbeit, zum Strassenbau oder aehnlichen Dingen jeweils von 3 zu 3 Monaten "datachieren" zu lassen. Diese Art von Taetigkeit gibt uns zwar das Recht, von den betreffenden Arbeitgeber recht und schlecht bekoestigt zu werden; keinen aber erlaubt sie, seine Frau oder Familie zu ernaehren. Diejenigen, welche nicht Prestataere waren, oder es nicht mehr sind - dies haengt mehr oder weniger vom Zufall ab - leben von den letzten Sous, die ihnen noch verblieben sind oder von Unterstuetzungen, und wer auch diese nicht mehr bekommt, muss damit rechnen, in irgend ein Lager gesteckt zu werden. Mindestens ebenso gross wie unsere rein materiellen Noete sind aber die moralischen. Denn seit Jahr und Tag unserem Beruf und unseren wissenschaftlichen und wirtschaftlichen Schaffen entrissen, sehen wir nicht, wann und wie wir einst den Weg zu einer geordneten Taetigkeit zurueckfinden sollen.

Fuer uns Intellektuelle ist es geradezu tragisch zu fuehlen, wie wir von Tag zu Tag mehr und mehr den Kontakt mit unseren Fachgebiet verlieren. Waehrend so unsere intellektuellen Kraefte brachliegen und unser Koennen und Wissen allmaehlich einrostet, haben wir doch das Bewusstsein, dass ausserhalb unseres Wirkungsbereichs weitergearbeitet wird, dass auf dem Gebiete der Chemie, der Physik, der Biologie, der Medizin, u.s.w. taeglich weiter geforscht wird und taeglich neue Entdeckungen und Erfindungen gemacht werden, an denen wir nicht nur keinen Anteil haben, sondern die nicht einmal zu unserer Kenntnis gelangen. Auch hier wirkt sich naemlich wieder unsere Notlage aus; denn gezwungen, auf kleinen Doerfern, fern von den Zentren geistiger Taetigkeit zu leben, besitzen wir nicht die erforderlichen Mittel, uns die wissenschaftliche Literatur zu besorgen, die uns ueber das gegenwaertige Schaffen auf unseren Fachgebieten unterrichten koennte .

Koennen Sie sich vorstellen, mit welchen Sorgen wir der Zukunft entgegensehen? Um es ganz schlicht und einfach auszudruecken: wir fuehlen, dass wir taeglich aelter, aermer und duemmer werden. Wenn es sich nur darum handelte, die gegenwaertige Kriegsperiode zu ueberstehen , muessten wir eben einfach "durchhalten". Aber wir fragen uns, sicher nicht mit Unrecht: was soll aus uns nach dem Kriege werden ? Selbstverstaendlich haengt sehr viel vom Ausgang des Krieges selbst ab. Aber wie dieser auch enden moege: wenn nicht all unser Wissen und Koennen der Wissenschaft und der

Image 2

(page 2)

Wirtschaft verlorengehen, wenn nicht soundsoviele einst gesicherte Existenzen einfach vernichtet werden sollen , dann muessen wir zumindest - trotz aller augenblicklichen Noete und Entbehrungen - wie man hier sagt „reserver notre avenir“, d. h. in unseren Falle: wir muessen dafuer sorgen, dass unser Wissen nicht vollkommen veraltet und dass wir an dem Tage, an dem wir wieder ins „roulement“ zugelassen werden, nicht auf einem toten Geleise stehen - reif zum Verschrotten .

Was nun getan werden koennte, um uns zu helfen? Meine Kollegen und ich, wir sind natuerlich alle von dem Wunsche beseelt, nach dort zu kommen, wo wir, wie wir wissen, unsere Arbeitskraft und Kenntnisse verwerten koennten. Wir sind uns aber der Schwierigkeiten des gegenwaertigen Zeitpunktes zu bewusst, um Sie zu bitten, eine Aktion in diesem Sinne fuer uns in die Wege zu leiten (so schoen es auch waere). Dagegen koennte uns vielleicht vor der Hand in anderer, einfacherer Weise geholfen werden, und zwar neben materieller Hilfe, die natuerlich sehr willkommen waere, durch Versorgung mit wissenschaftlicher Literatur ( Zeitschriften und Neuerscheinungen ) in englischer, deutscher oder franzoesischer Sprache auf den Gebieten der Chemie, Physik , Medizin, Biologie usw. Trotz der geschilderten Schwierigkeiten, die sich uns hier entgegenstellen, koennte vielleicht der eine oder andere meiner Kollegen oder auch ich selbst als Gegenleistung Uebersetzungen oder Berichte liefern ueber das, was gegenwertig hier auf den interessierenden Fachgebieten gearbeitet und veroeffentlicht wird. Es ist dies zwar recht duerftig im Vergleich zu der wissenschaftlichen Arbeit, die dort drueben geleistet wird; immerhin koennte aber Derartiges bei den einen oder anderen der dortigen Verleger oder Institute Beachtung finden.

Image 1

Excerpt of a letter from the chemist Erwin Hirsch, currently in Saint-Juery (Tarn), dated January 31, 1942, addressed to Stefan Jakobowicz, New York

We find ourselves in a melancholic situation. I do not want to tell you about things that you have already learned there, be it from the press or from consumer reports. Moreover, my personal worries and hardships should not be mentioned. On the other hand, I would like to draw your attention to the fate of a small group of people who are with me and find themselves in a situation that corresponds to mine.

As you probably learned at the time, I was actively employed at the “Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique” (National Center of Scientific Research) in Montpellier until the end of June 1940. We had 50 employees there, who were all scientists, especially chemists and physicists. This community was abolished. However, a small group of colleagues, all of Jewish descent and in the same situation, remains.

Our common plight is that we have been deprived of the right and the opportunity to pursue our profession. Many of us – including myself – have still not been removed, i.e., we have remained employees. Moreover, if we want to avoid being sent to a concentration camp, we have the possibility to do agricultural work, road construction, or other things from 2-3 months at a time. Although this kind of work gives us the right to be badly fed by the employers concerned, it does not allow anyone to feed their wife or family. Those who were not employees or are no longer - this depends more or less on chance - live from their last penny, or from other means of financial support. Whoever does not receive this support must come to terms with it or be placed in a concentration camp. In addition to the material hardships, moral woes exist. Despite everything, after having been robbed of our profession and our scientific and economic work for years and years, we do not see when and how we should resume normal employment one day.

For us intellectuals, it is downright tragic to feel how we are increasingly losing contact with our field of expertise every day. As our intellectual powers lie idle and our skills and knowledge become obsolete, we are aware that outside of our purview, research continues every day in the fields of chemistry, physics, biology, medicine, etc. In addition, new discoveries and inventions are made every day, in which we cannot participate or even know about. Again, our plight is in full swing. We are forced to live in small villages far from the centers of intellectual activity. We also do not have the necessary means to obtain the scientific literature, which could teach us about the current work in our fields.

Can you imagine what concerns we have for the future? To put it simply: we feel that we are becoming older, poorer, and dumber every day. If it were just a matter of surviving the current war, we would simply have to “persevere.” However, we ask ourselves, and certainly not in vain: what should become of us after the war? Of course, a great deal depends on the outcome of the war itself. If all our knowledge, scientific skills, and economic abilities are to be saved,

Image 2

(page 2)

and our once secure livelihoods are not to be simply destroyed, then we must at least - despite all the current hardships and deprivations - as they say here, “preserve our future.” In our case, this means we must ensure that our knowledge is not completely out of date and that on the day we are permitted to re-enter the working world, we will not be standing in a junk yard ripe for scrapping.

What could be done to help us? Of course, my colleagues and I are all inspired by the desire to come to where we know we can use our manpower and skills. However, we are all too aware of the difficulties of the present time to ask you to advocate for us in this sense. On the other hand, we could perhaps be helped in a different, simpler way through financial assistance, which would of course be very welcome, and the procurement of scientific literature (journals and new publications ) in English, German or French in the fields of chemistry, physics, medicine, biology, etc. Despite the aforementioned difficulties, which are affecting us adversely here, perhaps one of my colleagues or even I could provide translations or reports on what is currently being worked on and published here in various fields of interest. Although this is quite dubious compared to the scientific work that is done there, such things could be considered by one of the publishers or institutes there.